The Sonata for violin and bass violin ca. 1700

- Maximiliano Segura Sánchez

- Apr 18, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 19, 2021

PART II

Corellian influence

It is quite interesting to see how much influence and followers exerted Corelli’s Sonate a Violino e Violone o Cimbalo, Op.5 right after its publication. Pressed by the engraver Gasparo Pietra Santa in Rome in 1700, it is probably one of the most published books of instrumental music during the entire eighteenth century, with no less than fifty reprints. Just only in 1700 was reprinted in Amsterdam by Estienne Roger and by John Walsh in London. Looking at the IMSLP Petrucci’s online library page, we can find many editions and versions, among them very interesting ones such as Jeannette Roger’s 1723 reprint with Corelli’s (supposedly) ornaments or the one of Antonio Tonelli’s complete continuo realisation.

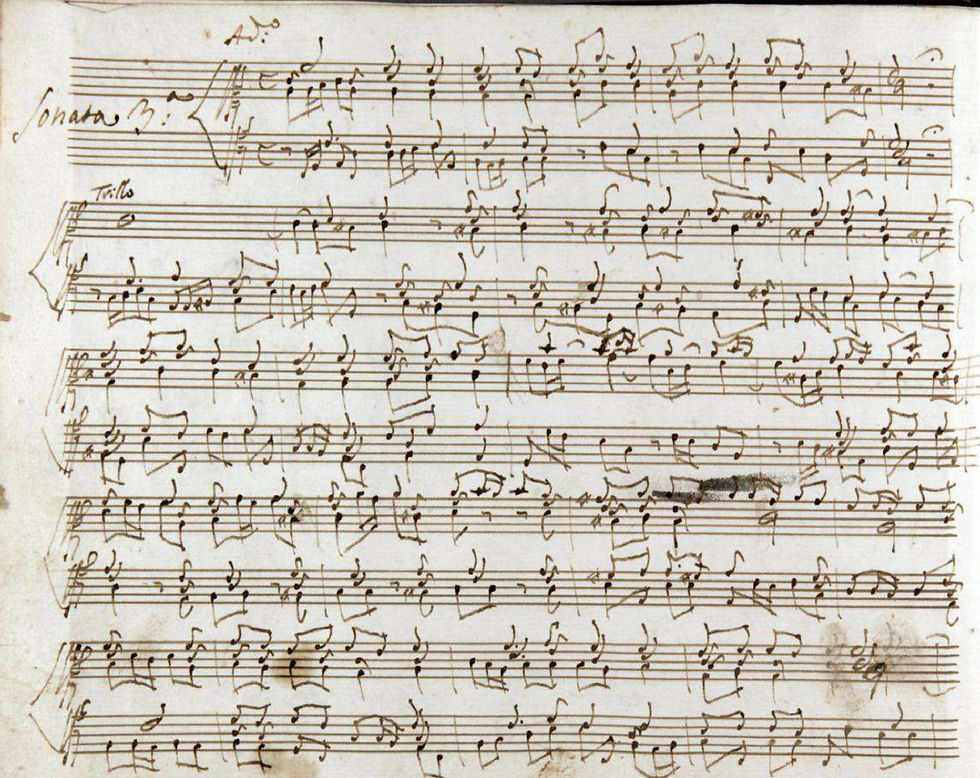

Example 1: Antonio Tonelli's continuo realisation of the Adagio from Corelli's third sonata Op.5. Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena, I-MOe. Mus.F.1174

These sonatas could present some problems of identification of whether are duos or violin sonatas with continuo. However, the title turns to indicate the pieces as “duos” in almost its strict meaning, a Violino e Violone, like the collections mentioned in the previous post. In addition to that, the violone part presents very idiomatic language for the instrument in most of the sonatas, especially in La Follia variations. Not a few collections followed the same pattern and style. For example, Corelli’s pupils Giovanni Mossi’s Sonate a Violino e Violone o Cimbalo, Op.1, 1716, Francesco Geminiani’s Sonate a Violino, Violone, e Cembalo, Op.1, 1716, Pietro Castrucci’s Sonate a Violino e Violone, o Cimbalo, Op.1, 1718, were influenced by his master’s style and technique.

Mossi’s sonatas follow consistently his master steps in the division of movements and structure in the collection. The book is divided in two parts, first one dedicated to non dance-movements sonatas and a second with a “da camera” configuration. The choice of dance movements is consistent in most of the sonatas, with an average of three to five movements. The whole constitutes a good example of Corelli’s shadow into his students. Not surprisingly, these elements appear as the norm and not as the exemption in many composers who imitated the Roman master. The first half dedicated to non dance-movements uses the fugue-form in most of his second movements, as Corelli does. His last movements contain as well entrances in dialogue with the basso continuo and the violin itself, outlining three voice fugues.

Example 2: Giovanni Mossi, Allegro from Sonata I, Sonate a Violino e Violone o Cimbalo, Op.1, Amsterdam 1716, Jeanne Roger

Geminiani’s sonatas do not add specific dance-movements, although we found traces of Allemandes, Gigues or Gavottes. The use of fugues in second movements appear in the first six sonatas, providing a division of the book in two halves, like in the other collections.

Pietro Castrucci presents a different insight in his opera prima. In contrast with Corelli, Mossi and, to some degree, Geminiani, Castrucci incorporates light harmonic language and provides to the violin more melodic material, relegating the bass to an accompaniment role. In terms of form, the sonatas are freer, mixing non dance-movements with an Allemande, Gigue, or Gavotte, and presenting other features, such as scordatura in the last sonata.

A lesser known student of Il Bolognese was Gasparo Visconti who, like Castrucci and Geminiani, lived in London for some years gaining modest fame. His Sonate a Violino e Violone o Cembalo, Op.1 were engraved by Roger as early as 1703. Sonatas one till four follow a “da camera” structure with a more or less standard order. From sonata five, the language becomes more counterpoint-oriented, involving the violone in the musical schema, a good example of it being the Allegro in Sonata Quinta. The last sonata is written for two violins, however cannot not be labelled as a proper trio sonata, since the second violin works as a ripieno together with the bass, producing a false effect of a violin concerto.

A violinist to outline is the Neapolitan Michele Mascitti who left a significant quantity of repertoire. Presumably Corelli’s student, however no documents can confirm such assumption. It could have been in contact with the Roman master when Corelli visited Naples in 1702 to supervise performances organized to celebrate the visit of Philip V of Spain. Based in Paris from 1704 until his death, we find no less than eight collections of violin and trio sonatas, some of them labelled à Violino solo col violone o cembalo. The publishing of his Op.1, Op.2, and Op.3, between 1704 and 1707, shows the popularity of his music within the French audience. Mascitti, basing his books in the Corellian model and with a Neapolitan background (was a student of Pietro Marchitelli), is a central figure in spreading Italian instrumental forms in France in the first decades of the eighteenth century.

Example 3: Michele Mascitti, Allegro from Sonata VI, Sonate da Camera a Violino solo col violone o cembalo, Op.2, Paris 1706, Foucout

The influence of Corelli’s book appeared too among his Roman colleagues, such as in Giuseppe Valentini’s seven Idee per Camera a Violino e Violone o Cembalo, Op.4 published, again by Roger, in 1706. Nonetheless, Valentini does not follow Corelli’s model as a foundation. Writing an average of five to seven movements per “Idee,” no dance-movements appear, as it should be when labeling the pieces as da camera. Next to this, his Allettamenti per Camera a Violino e Violoncello, o Cembalo, Op.8, published in Rome in 1714, and reprinted by Le Cene in Amsterdam and Walsh in London, proving the popularity of Valentini’s music. These pieces feature some dialogue between both instruments, including a demanding passage for the cello at the Allegro in the sixth Allettamento. These sixteenth-note arpeggiated passages occur often in cello passages written by cellist-composers such as Bononcini (Valentini’s teacher), Jacchini and Caldara.

Example 4: Giuseppe Valentini, Allegro from Allettamento VI, Allettamenti per Camera a Violino e Violoncello, o Cembalo, Op.8, Rome 1714, Mascardi; edition by Estienne Roger and Michel Charles Le Cene, Amsterdam 1714

Another string player to recall as a possible “victim” within the side effects of Corelli’s Op.5 is Evaristo Felice Dall’Abaco, probably trained on the violin and cello in his hometown, Verona, by Torelli. He was active in Modena, a city for cello music, until he definitely left Italy in 1704, like Mascitti. Two collections are devoted to the violin and bass violin: Sonate da Camera a Violino e Violoncello overo Clavicembalo solo, Op.1, published ca. 1708 and Sonate da Camera a Violino e Violoncello, Op.4, 1716. In his Op.1 the importance of the violoncello part is highlighted, defining the lines of both instruments. No continuo figurations appear in the cello part, meaning anything at all, since we see no figures in collections featuring the harpsichord as a chordal instrument. However, the idiomatic cello part, like in the Largo Andante in Sonata ten, give us clues to consider these pieces, without objection, as duos. It may be Corelli’s Op.5 the model followed by Dall’Abaco, probably in terms of commercial intuition. Nevertheless, stylistically speaking, his sonatas follow more the model of his Emilian colleagues, such as Torelli’s Op.4 and Tomaso Antonio Vitali’s Op.4.

Example 5: Evaristo Felice Dall'Abaco, Largo Andante from Sonata X, Sonate da Camera a Violino e Violoncello overo Clavicembalo solo, Op.1, Amsterdam ca. 1708, Estienne Roger

Vitali’s Concerto di Sonate a Violino, Violoncello e Cembalo Op.4, Modena 1701, is a collection to take into consideration. In contrast with the rest, the book has parts and not a score, probably due to the fact that it is pressed by the movable-type technique. The book contains three parts, being the violoncello independent from the harpsichord and involved in the violin’s thematic material. This collection may have served Dall’Abaco as a model for his Op.1. Published a year after Corelli’s Op.5 and dedicated to Cardinal Ottoboni, may indicate a certain debt with the Roman since the last sonata presents a set of La Follia variations.

Of course, it is obliged to mention Vivaldi’s contribution to the genre with his Sonate a Violino e Basso per il Cembalo, Op.2, Venice 1709. Mentioning the harpsichord as the bass option may not be exclusive to the chordal instrument since the bass dialogues with the violin part and features many of the characteristics of the sonatas a “violino e violone.” The Presto in the second, Allemande in the fourth, the Preludio in the seventh and the Capriccio in the ninth sonata present examples of the possible use of a bass violin in demanding passages. In contrast to Vivaldi, in Tomaso Albinoni’s Sonate da Chiesa a Violino Solo e Violoncello o Basso Continuo, Op.4, Amsterdam ca. 1708, the violoncello part is a mere bass sustain, not contributing with virtuosity.

To conclude with this post, as observed, the sonata for violin and bass violin appeared rather often in the first decades of the eighteenth century through Italian composers related or influenced by Corelli’s Op.5. Sometimes it is difficult to define the line in which the bass violin part develops as an accompaniment or as a second voice in the musical dialogue. The repertoire cannot be resumed in the pieces presented in this text, since we cannot reduce the spread of this genre in just Corelli’s impact. His legacy into the forthcoming generations implied mostly a stylistic approach, and too opened the opportunity to show the musical skills of many violinists-composers in some of their operas prima.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALLSOP, P., Arcangelo Corelli: New Orpheus of Our Times, Oxford University Press, 1999

OLIVIERI, G., s.v. MASCITTI, Michelle, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 71 (2008)

ANTOLINI, B.M., s.v. DALL’ABACO, Evaristo Felice, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 31 (1985)

Primary sources, chronologically ordered:

Corelli, A., Sonate a Violino e Violone o cimbalo, Op.5, Rome 1700, Gasparo Pietra Santa

Vitali, T.A., Concerto di Sonate a Violino, Violoncello, e Cembalo, Modena 1701, Fortuniano Rosati

Visconti, G., Sonate a Violino e Violone o cembalo, Op.1, Amsterdam 1703, Estienne Roger

Mascitti, M., Sonate a Violino Solo col Violone o Cimbalo e Sonate A due Violini, Violoncello, e Basso Continuo, Op.1, Paris 1704, Foucaut

Mascitti, M., Sonate da camera a Violino Solo Col Violone o Cimbalo, Op.2, Paris 1706, Foucaut

Valentini, G., Idee per Camera a Violino, e Violone, o Cembalo, Op.4, Amsterdam 1706, Estienne Roger

Mascitti, M., Sonate da camera a violino solo col violone o cembalo, Op.3, Paris 1707, Foucaut

Dall'Abaco, E.F., Sonate da Camera, a Violino e Violoncello, overo Clavicembalo solo, Op.1, Amsterdam ca. 1708, Estienne Roger

Albinoni, T., Sonate da chiesa a violino solo e violoncello o basso continuo, Op.4, Amsterdam ca. 1708, Estienne Roger

Vivaldi, A., Sonate a violino e basso per il cembalo, Op.2, Venice ca. 1709, Antonio Bortoli, repr. Amsterdam ca. 1711, Estienne Roger

Valentini, G., Allettamenti da Camera a violini e violoncello o cembalo, Op.8, Rome 1714, Il Mascardi

Mossi, G., Sonate a Violino e Violone o Cimbalo, Op.1, Amsterdam 1716, Jeanne Roger

Geminiani, F., Sonate a Violino, Violone e Cembalo, Op.1, London 1716, n.n.

Castrucci, P., Sonate a Violino e Violone, o Cimbalo, Op.1, Amsterdam 1718, Jeanne Roger

Comments